We're back for the September edition of our Creator Spotlight series, where we shine a light on working creative professionals, and give them a chance to share part of their story, their learnings, their favorite tools, and more. This month, we're really grateful to be chatting with Cristina Mittermeier, or "Mitty" - a marine biologist and photographer who's accomplishments and accolades are seemingly endless! She is a Sony Artisan of Imagery, a National Geographic Explorer, pioneered the field of Conservation Photography and founded the International League of Conservation Photography, co-founded SeaLegacy with her husband Paul Nicklen, and the list goes on. Read this detailed look at Cristina Mittermeier's truly inspiring journey below!

Cristina Mittermeier - thank you so much for taking the time. If you were meeting a stranger and they asked you, "Who are you and what do you do?", what's your quick elevator pitch about yourself?

I usually lead with ‘I'm a National Geographic photographer’ because that is something that usually gets people's attention. If I just say I'm a photographer, you can lose people's interests very quickly. I think people are genuinely interested in what a National Geographic photographer is and does… so I usually lead with that, and then I follow up with, ‘I work in ocean conservation and championing the rights of women, the rights of Indigenous people, the rights of nature, and so forth.’ And then I tell them I'm a marine biologist and they go, “oOo, ah!”, and people are funny, because they often say “I always wanted to be a marine biologist” or “I really thought about being a photographer and I didn't do it”, so I'm very grateful that I got to live it.

Photo provided courtesy of Cristina Mittermeier. ©

Photo provided courtesy of Cristina Mittermeier. ©I think your journey is so inspiring to many, and hopefully there are young people who read your story, and are inspired to not go the route that maybe their family or their society is telling them they should go, and instead go the route that their heart is calling them to. I know that you grew up in Mexico. Where was the original passion found and how did you start to pull on that thread?

I grew up in the mountains of Central Mexico, but my dad is from the Gulf of Mexico, from a small city called Tampico. It’s almost on the border with Texas. We used to go and visit his family there, and that was my first introduction to the ocean. It was not the most beautiful beach. There are a lot of oil rigs on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, so there’s usually a lot of tar. My mom used to have to bring gasoline to clean our feet after going to the beach.

I think that was the first thread, and then books, and of course National Geographic magazine - but mostly pirate books, believe it or not! I read these adventure stories about pirates in Malaysia, and they were beautifully written. The descriptions were so vivid, sharks and crocodiles and tigers in the jungle. I think that really awakened this feeling that I wanted to have that kind of adventure. Of course, the answer from my father was, “No! Absolutely, you're not going to be a marine biologist. Biologists starve.” I was very lucky that my mom championed me. She said, “Go and do whatever you want, and I'll deal with your dad.” And she did. That's amazing.

Photo provided courtesy of Cristina Mittermeier. ©

Photo provided courtesy of Cristina Mittermeier. ©You started studying marine biology. At what point did cameras get into the mix?

I think that the education system somehow expects us to know what we want to do with the rest of our lives in our first year of university, but I dabbled. I studied a little bit about Plankton. I spent a lot of time looking at the ocean through a microscope - realized I didn't want to work in a lab, but the thing that was revealed is the diversity of life in a microscopic way, and that is the engine of life on planet Earth. I also studied whales. The Gulf of California, where I went to university, has a large diversity of whales, and I think that was my first fascination with these large animals.

I also studied aquaculture and fisheries. I have this innate sense of social justice and the preoccupation of, ‘How are we going to feed the planet?’, and understanding that the industrial hunting of ocean wildlife is just a very stupid idea. We don't hunt bears and cougars and tigers for the grocery store meat shelf, so why do we think that tuna and salmon are okay? If we're going to feed the planet it's going to be from aquaculture and fisheries, so that's the route that I went.

My first job was not what I wanted to do, but oftentimes when you graduate university you take the first thing that comes. I accepted a job at a hotel doing a biodiversity assessment in the Yucatan Peninsula. It was zero pay, just an exchange for room and board. They had a dive shop, so I spent the year diving every day, running in the jungle, catching butterflies.

It was a magical year, but my father was like, “You're not going to get paid?!”, and that's what led me to my first job at Conservation International, which was a very new organization in the 1980s. I got a job in Mexico City, and it was a bad job but we were sharing an office space with a photographer. It was the first time that I got to see what a photographer does. He was a Mexican photographer, Patricio Robles Gil, and I would just walk by his office and see what he was doing. He was making books and calendars for corporations about the natural world. So that's the first time that I thought, “You know what, maybe photography is a good way to communicate with audiences that are not necessarily receptive to what's happening to nature!”

Amazing. Your Wikipedia page says that your images “focus on demonstrating the relationship between human cultures, indigenous people, and biodiversity to ocean and climate change.” Can you talk about that relationship a little bit?

In my first attempt at photography, I was confronted with a very difficult decision. I wanted to be a wildlife photographer, but I got married really, really young, and I had my first child when I was 23 - so the dream of going to shoot bears or whatever was very far-fetched. But I was married to an anthropologist, and he would travel to these remote villages, so that's how I started taking photographs of Indigenous people. That was the opportunity I had at that time.

In the 1980’s and the early 1990’s, the conservation community had postulated that we needed to remove human interference from ecosystems in order for them to be protected, so Indigenous people were being forcibly removed from their ancestral lands to create National Parks. (laughs) You believe that? So it was in the 1990’s the realization happened that you cannot succeed at protecting something unless you partner and collaborate with the people who have always lived there - and in most cases, that's Indigenous people. That's how I [ended up] spending a lot of time with Indigenous people, and listening to not just their knowledge of the ecosystems where they live but also their value system. All Indigenous people around the world have a value system that makes them relations to the natural world - it's something that is related to you, so it's not something to be exploited.

My goodness, that shifts the whole way that you look at things, right? Tsleil-Waututh of the first nations here in British Columbia said to me, “Oh, the rock, the mountain, the raven, the bear, my grandmother, me - we're all made of the same material, we're all related.”

That was my first inkling, and I am very lucky that I'm still working on photography with Indigenous people - trying to elevate the values and the voices. I was at the Wilderness Congress last week, and it was convened by the Lakota First Nations. It was the first time in history that an Indigenous group had convened the conservation Congress, which is incredible. I was saying to them, every head of state should have two people sitting at their cabinet at all times, an Indigenous elder and a biologist. These heads of state, you know, they know a lot about the economy and those kinds of things, but they don't know how to captain the ship.

I also get to live the life of the wildlife photographer because my second husband is one of the most iconic wildlife photographers in the world! He's not just incredible with animals, he's also an amazing diver and so I got to live the dream of the underwater photographer too!

Your body of work speaks for itself. There's a lot of wildlife photography. There's also a lot of absolutely breathtaking portrait photography. So, when you approach different types of photography, do you take a different approach or do you approach them with the same curiosity? Is there a difference in the approach when you're working with animals versus humans?

I think at the core of my creativity, I am a portrait maker. I think I bring the same curiosity about what's behind the eyes of an animal and the eyes of a person. I think I have this deep desire to know what's behind, and I think that curiosity is a very good driver for portrait photographers, because you're looking for a gesture, you're looking for a stare, you're looking for a very brief moment of interaction in a photograph that is everything.

Are there any particular photographs that you've taken - or projects - that are particularly close to your heart?

So many. When I started portraiture many, many years ago, I was very nervous. One of the most difficult things that a photographer has to overcome is a reluctance to enter another being's private space. It's so difficult to get comfortable putting a camera in front of somebody and it took me a long time. But once you overcome that, and you start getting more comfortable, then you can start asking a lot of questions about the person you're photographing.

To me, those are the most beautiful and valuable relationships because I have made so many friends around the world. We forget that Indigenous people, for the most part, live and work amongst us. They're not wearing their regalia every day. They’re friends on Facebook, all over the world, and there's an allyship happening between indigenous communities, between people who are not indigenous but who really want to support the system of values, and then all of us being allies to our planet. This allyship is something so beautiful.

That's awesome. My first exposure to indigenous communities, because, you know, in the American school system, you grow up to believe that indigenous people are one thing. You’re not taught about the nuance of all the different communities. I had the pleasure of attending an Aniwa Gathering years ago where my eyes were opened in a big way to the depth of the different cultures - how they differ, and where they overlap. I sat with a Maori elder for two hours in a men's circle and it was so life-changing, so transformational.

To comment on that, it is true that a lot of Indigenous groups have a Men’s council. In a lot of places, women are not invited into the same spaces and the council is almost always men. In the beginning, I thought ‘Well, that's going to be a real handicap if I'm not allowed in the men's house to photograph what's happening’ and then the door opened and I thought ‘Ah, maybe I can have access to the secret life of women who are these whole other important component of every society.’ and so that's where I focus my lens for the most part - the sisterhood, really.

Perfect segue to my next question about your experience as a woman in the industry. What are some of the challenges you’ve faced? Do you want to talk about some of the pros and cons of being a female in the industry?

Remember that I started my career in the 1990s. Back then, it really truly was a very white, middle-aged male dominated profession, in the United States especially - and women like myself were not taken very seriously. I think of the two worst handicaps that I've had in my career - one was being a Mexican and the second one was being a woman - being a woman was way harder.

You can either complain and you can sulk because you're not being included, or you can assume that you're going to be underestimated. Then you can fly under the radar, do your thing and surprise everybody with what you can do - and that's what I did! I thought, ‘why am I going to butt heads with all of these buttheads? I'm just going to do my thing and then they'll see who I really am.’ Along the way, you learn that not all men are willing to exclude women. A lot of them want to be allies and they want to help, and it is important for women to accept help. I got incredible help from some of my male colleagues along the way, and I’m so grateful that they were willing to champion me, teach me, mentor me, push me.

I love that. I think it's important for that allyship to exist on so many different levels in the industry. So speaking of doing your thing - you pioneered the field of conservation photography. We've already kind of touched on what the concept means to you, but could you elaborate?

I can tell you a couple of things about it. I wanted to find a lane in photography that I could call my own, and I could see that wildlife photography was very crowded with very talented, very capable men wielding big cameras and big lenses - and I thought it's going to be really hard for me to compete there. The idea of using the skills and creativity to actually protect the places and the things that we photographed was really attractive to me - so that was the impetus for defining what's the difference between being a nature photographer and being a conservation photographer. It's this element of activism. Taking the photographs alone is not enough. You have to be willing to grab those photographs and do the work of whatever is necessary for the people that make the decisions to see those photographs and understand why.

That was the impetus for the creation of the International League of Conservation Photography, as well as the field of conservation photography. I created a lane for myself. I thought, you know, ‘I can work here.’ I needed a lane where I could include my passion for indigenous people, passion for my life and the passion for the ocean. It all lives underneath.

You've done work now with quite a few nonprofits or NGOs. It's been an amazing evolution. Can you can you give a brief insight into how you went from Conservation International to ILCP, and then Sea Legacy more recently?

Conservation International was my first ever job and I held a couple of positions there. Eventually, I became Director of Visual Communications at CI. That was the first time that I realized that communications is so incredibly underfunded in the NGO world. There almost never is a budget to send a photographer or a film crew. To this day, it’s really difficult - so I made it my life's mission to scream as loud as I can:

“We cannot move the needle on conserving anything if people don't know about it.” We need to create philanthropy around this type of activity, and it's been so challenging, Eric. So difficult to this day. But Conservation International taught me so much about how conservation works. It's all about diplomacy. All about relationships. Eventually I was able to start my own nonprofit, the International League of Conservation Photographers.

After I met Paul, we decided that we needed to start our own non-profit so that we could tell the stories the way we wanted to tell them - and try to raise the money to do it, and demonstrate that Communications is an integral part of the toolkit and we need to make investments into it.

Photo provided courtesy of Cristina Mittermeier. ©

Photo provided courtesy of Cristina Mittermeier. ©I'm curious if you're willing to share how that relationship evolved. There's a camaraderie and so much more depth in the relationship.

We met in the cafeteria of National Geographic. We first became colleagues and started working together on assignments and eventually we became a couple. We've been together for almost 14 years and the relationship is so complimentary.

Paul is the ultimate expedition leader because he did that for NatGeo for so many years. He's capable of organizing us to be in the right place at the right time with the right equipment to get the job done. I am the conservation diplomat, so I'm always thinking: what are the levers that we can pull? What are the relationships with policymakers or with NGOs that we can create? So that we can use media to move the needle, and we constantly work in this yin and yang of getting the visuals and then making them useful - and it's so much fun. We do a lot of public speaking together and we talk about his journey, my journey. He's a marine biologist turned photographer just like me, and we just have the most blessed, lucky life. We live in British Columbia, in a beautiful house by the ocean with our dogs. (laughs) We get paid to do what we love and to make a difference. I often tell Paul that a lot of it would not taste so sweet if I didn't have him to share it with. We're so lucky. We were both married to other people for 20 years before we met each other, so we both understand what it is like to be in a marriage where you're not understood or complimented - and the freedom you get when you are. I mean, there's two kinds of people - there are anchors and there are sails, and I found my sail with Paul.

That's really profound. You two are incredible. You talked about being a positive role model as a female creative. You guys are also creating a positive role model of what an empowered and adventurous marriage can look like.

You know - we’re both going to be 60 in the next 2-3 years, and we’ve had these candid conversations about what that means. I don't want to be that ridiculous older couple still trying to dive and chasing sharks. There's a time to kind of quiet down and make different objectives for your career. So for us, it feels so liberating to be able to say, ‘Okay, the next 10 years of our lives, let's dedicate them to make art.’ We've already done the grind of National Geographic editorial. We've already done the grind of setting up a nonprofit that's very successful. Now, let's just be artists! And you know what? The artists exist to fuel the revolution. To make it irresistible! So we have a big role to play as artists.

We touched on Sea Legacy a bit, and I think this is a perfect example of artists starting the revolution through the work that you do. Glyph has been very grateful to be able to support that work. Can you talk about the recent expedition and what Sea Legacy means to you?

So good to us, thank you. We have been on an expedition, around the world really. We bought the boat. It's a personal purchase, Paul and I, for freedom. We just want to have the freedom to be out there telling stories - and the boat's going around the world, so recently it sailed from Mexico to French Polynesia and then to New Zealand, then we crossed the Tasman Sea into Australia. We spent time in the Great Barrier Reef documenting the latest bleaching that happened, which was devastating. Now the boat is on its way to Indonesia. We're going to spend the next nine months in the Indonesian area, filming and documenting. There's so many great stories there… rewilding, introduction of sharks. I want to see what's happening with the coral reefs. There's a lot of community-based conservation in Indonesia.

Our goal is to do something similar to what we did in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, where we supported Conservation International and other organizations to push for the creation of an interconnected swimway between Panama, Colombia, Costa Rica and Ecuador. All these animals that migrate- the minute they leave Marine National Park, the fishing fleet is waiting outside - so we were able to help create this swimway. Now we have the opportunity to do something similar between Australia, Indonesia and Timor-Leste, where you have these massive migrations of whales, even crocodiles, sharks, sea turtles, and taking the opportunity to ignite the curiosity and the conversation in these three countries.

I'm curious, from your perspective - what are some of the things that you're most proud of, that you've accomplished so far in your career?

So there's two parallel lines, the accomplishments that have to do with conservation and actually winning some of those battles. Nothing ever tastes more sweet than being part of a team, a group of people around the globe that's pushing for something that gets passed. You know, creation of a new marine protected area, or the uplifting of a species or whatever it is, that's the sweetest.

But on the photography side, of course, as creatives, you know, we have a number of summits that we need to climb, and being able to work for a magazine like National Geographic has been one of the greatest honors of my life. Having a byline in that magazine just feels like you reached the summit of Everest, and then you need to reach a different one. I really, I'm very proud to be such a well-paid female photographer because I don't care about money, but I do care about establishing or blazing a trail for the female photographers that are coming behind me, and mentoring them to be good business women who value their work.

And then I really think that photography needs to be elevated as an art form, so achieving something like getting a solo museum exhibit in Torino in Italy, being a collection in a museum. That is a huge achievement, not just for myself, but for our profession as a whole. And the latest one is that I have been invited to be the cultural ambassador to Davos, to the World Economic Forum - where the world leaders, the corporate leaders are coming to discuss the future of our planet, and I get to have something that I can share with them about what I think.

You're also a Sony Artisan. Can you talk about what it means to have such strong support from such an incredible brand and leader in the industry?

You know, I was incredibly lucky early in my career and I think looking back - you succeed or fail in your career based on the relationships you keep. I was selected to be one of the first six Artisans when Sony started their program because of the relationships I had, and I understand that without Sony, I would not have the career that I have today. They have been nothing but incredibly supportive. They have listened to all of my concerns in the beginning with environmental issues. If you open a Sony camera today, you will find that the packaging is all recyclable. It's like an origami box made out of recycled cardboard. I love knowing that I had a little bit of a part to play in creating something like that, you know, the way that the batteries have a full circle life now. We don't want anything to end up in the landfill.

Same can be said for Rolex, you know, Rolex and Perpetual Planet have given me full opening to their PR machine to talk to CNN, to talk to TIME, to put the environment and the ocean at the top of the media agenda… so I'm just so, so grateful.

Photo provided courtesy of Cristina Mittermeier. ©

Photo provided courtesy of Cristina Mittermeier. ©We've seen the explosion of tourism in places like Tulum and the devastating effects that this has had on the ecosystem. Do you find that the Indonesian government is doing a better job of handling the explosion of tourism?

No, Tulum was devastating to watch because that's where I had my first job in the 1990s, the early 1990s, just north of Tulum in Akumal, and over the next 25 years, it went from little tiny little huts in the beach to now there's resorts, and it never had the sewage infrastructure to deal with so many people, so it literally has become a shithole. It is stinky, it is messy, and it's horrible. Tourism destroyed it. The beautiful location that it used to be, the beaches, I don't know if you've been - they’re covered in sargassum, it's horrible, and Bali is very similar.

I recently watched the documentary that I recommend at We All Watch. It's called The Last Tourist. It is just a look at ourselves and the way we consume tourism so that we can become a little more aware and a little better stewards of the places we visit.

Okay, we’re down to our last few questions. I know that you must shoot multiple terabytes of data on every trip. Can you talk about how you deal with such large amounts of data?

I sure do. I am very grateful for our Glyph drives. I keep them taped to my computer and I work on projects off individual hard drives that then are backed up into a larger RAID system and into our server. Having the support of a company like Glyph helping us with a handful of these little hard drives makes an enormous difference because of the way we travel and because of the way we work. Both Paul and I tend to be really overwhelmingly disorganized, so dedicating an individual Atom Pro to a single project is a game changer. We put a little label on it and keep drawers full of these hard drives as additional backups really. I think about it as my original.

Okay, time for rapid fire - what are three must have pieces of kit?

I need my camera, my lenses. I really love the new Sony 20-70. It's a good zoom range. And then, of course, my external hard drives and my card readers - these are things that you must always have. A good multi battery charger too.

Ok, perfect. I also heard you're working on a book?

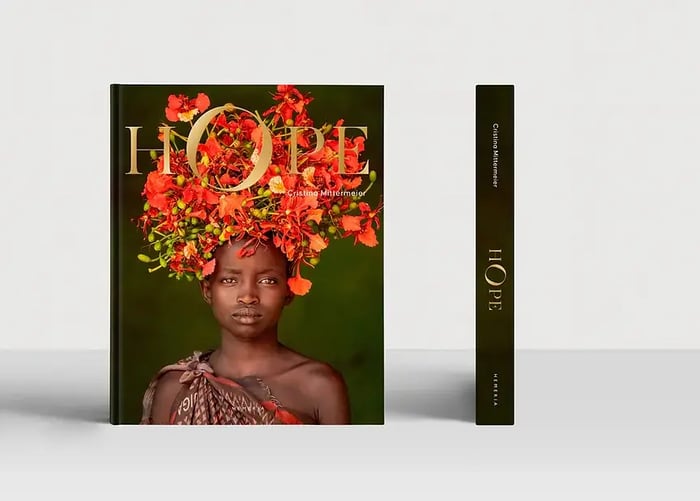

Of course, HOPE is my new book. Working in the front lines of conservation can be really depressing and really hard, and so I decided to create a monograph, a retrospective of my work - and call it HOPE because I need to have something to hold on that reminds me that there's a lot of good things happening in the world. There's a lot of heroes working for change everywhere, and we need to lean on each other for hope. So, HOPE is going to be beautiful.

It was published with crowdfunding. My followers helped me make a reality and it's coming out literally in the next couple of weeks. Such a beautiful book. It was the book of my dreams and my followers made it happen. It’s going to be in bookstores in Europe, and we're going to be selling it on my website with a pretty heavy social media campaign as well.

One of the great things about it is that some of the money that I make from the book, I send back to the villages and the people that I photograph.

Photo provided courtesy of Cristina Mittermeier. ©

Photo provided courtesy of Cristina Mittermeier. ©I'm pre-ordering a copy as soon as we wrap up. The last question is, what are some words of advice for someone who wants to do what you do?

Being a creative is a lifelong pursuit, so the best advice I can give somebody is to engage quickly into goal setting. Goal setting is one of the most powerful things that we can do because it provides you with a north star of where you want to go, and you will struggle throughout a lifelong career in creativity. It's a difficult journey, but if you have a north star of what it is that you want your life to look like - then you're able to overcome all the obstacles.

Since I cannot mentor people individually, I did a MASTERS OF PHOTOGRAPHY course where I talk about everything I know about establishing a successful career as a purpose driven photographer. Being a mom, raising children, establishing a nonprofit, working for National Geographic - all of it is in there. I highly recommend that young people who are interested in doing what I do have a look at that course.

Amazing. Cristina, it has been such a distinct pleasure to talk to you. Appreciate your time and all you do for the creative community and the world.

Thank you for all you do in the world of conservation, and take care.

Please make sure to go follow Cristina Mittermeier aka Mitty on Instagram, as well as SeaLegacy. All photos provided courtesy of Cristina Mittermeier. ©